The Good Ol’ Canadian Hockey Game

“Oh take me where, the hockey players, face off down the rink.

And the Stanley Cup, is all filled up, for the champs who win the drink.

Now the final flick, of a hockey stick, and the one gigantic scream.

”The puck is in! The home team wins!”, the good ol’ hockey game.”

For many Canadians, hockey is a part of our identity. The Brown Homestead has seen its share of both victory and heartbreak when it comes to the good ol’ hockey game, having been home to multiple generations of hockey-lovers throughout the 20th century. As we are well into the 2022 Stanley Cup playoffs, we wanted to offer our readers some insight into the history of hockey and its roots in Canadian nationalism.

The Stanley Cup

Introduction

On May 2nd, 2022, the National Hockey League (NHL) kicked off their annual playoffs for the Stanley Cup, which is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious sporting awards and recognized as the oldest existing trophy to be awarded to a professional sports franchise in North America. The deep roots of this competition, stretching back even beyond the founding of the NHL in 1917, have long been connected to acknowledging and rewarding the best hockey players in the world. However, for Canadians, the relationship that we have to the Stanley Cup is remarkably different. Despite no Canadian team winning the Cup since the Montreal Canadiens in 1993, there is a common argument that since the majority of the NHL (around 45% in 2022) is composed of Canadian players, Canada wins the cup every year. Canadian supremacy in hockey hinges on this technicality; on the idea that American teams are only American in name and not culture, which for many solidifies Canada’s place as the foremost home of hockey. This claim to ownership that Canadians feel over the sport of hockey is a long-held tradition that harkens back to the late nineteenth century, when organized ice hockey was just emerging as the game that we would more closely associate with our modern sport.

The Montreal Canadiens’ last Stanley Cup win in 1993

Hockey History

Though the origins of the modern game of ice hockey are debated, it is generally agreed upon that the first formally organized game of hockey took place in March of 1875 in Montreal (1). A brief article in The Montreal Gazette announced the game and stated that, “Good fun may be expected,” for spectators (2). Hockey, in its original and off-ice form originated from stick and ball games played across the United Kingdom and Ireland. However, as argued by Michael A. Robidoux, many traditions of hockey’s style of fast, aggressive, and violent play, were more so reflected in Indigenous sports like baggataway (modern day lacrosse), than in any colonial British sports like cricket (3). Despite these Indigenous roots, the teamplay and culture that surrounded sports in the late nineteenth century was still a distinctly British one. Hockey emerged as the middle ground between two sporting cultures, creating something that, perhaps for the first time, felt uniquely Canadian; and as such, would develop from these humble beginnings to become a major component of the Canadian search for identity throughout the twentieth century. So, while hockey did not necessarily originate in Canada, there is no question of its long held importance in Canadian culture. As perhaps summarized most effectively by Canadian NHL players Johnathan Toews and Sidney Crosby at the 2016 World Cup of Hockey, “Canada didn’t invent hockey, hockey invented Canada”(4). This invention of the relationship between hockey and Canada is also an invention of nationalism.

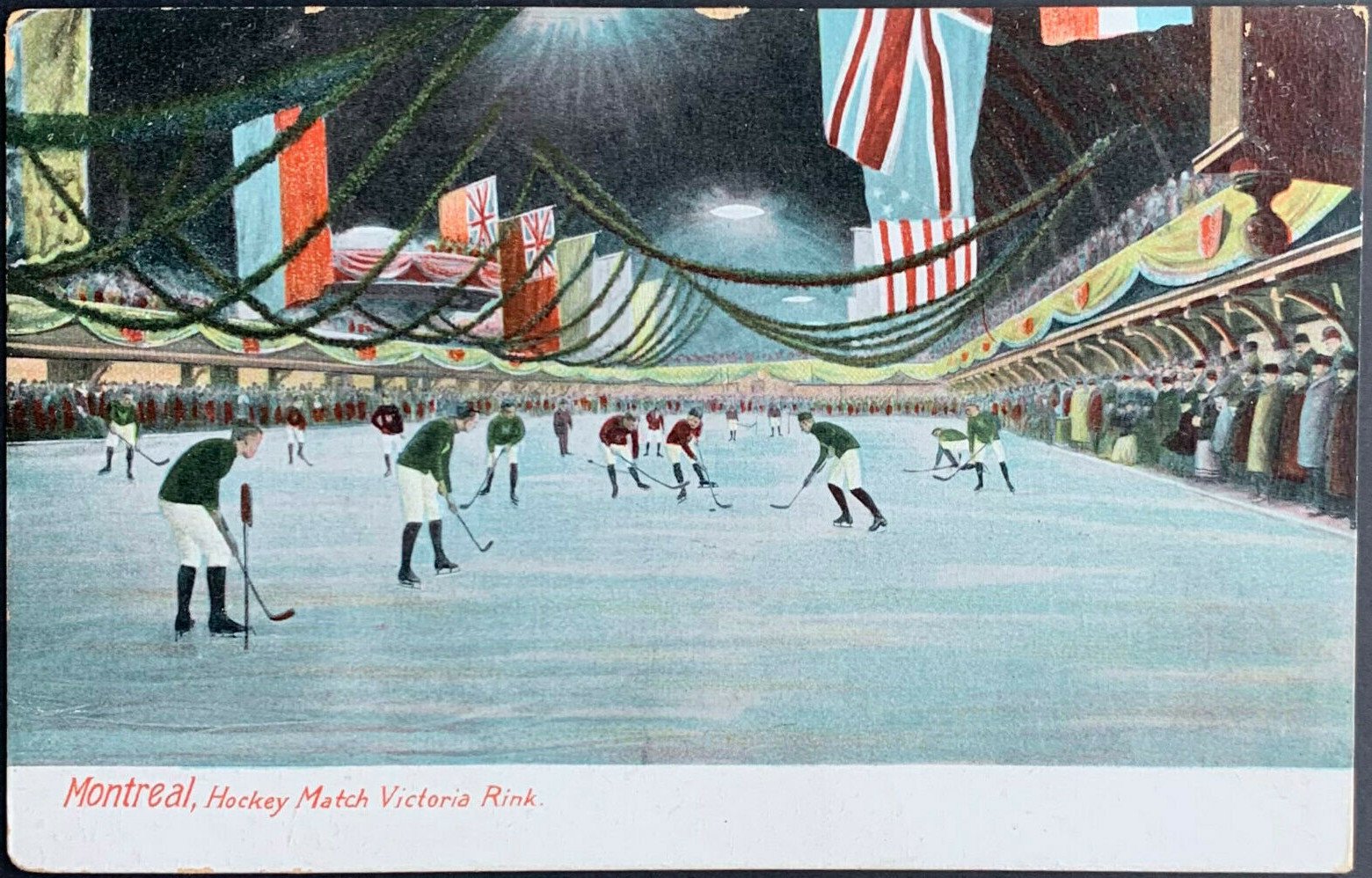

Postcard featuring the first indoor game of ice hockey in 1875

Canadian Identity

The establishment of Canadian nationalism met several major challenges immediately following Confederation in 1867. First, Canada is a vast land, with a small population over a large geographical space. The distance between those in the Atlantic provinces and the far west coast in British Columbia can lead to a sense of detachment between these groups of people, who may find it more appropriate to lay claim to a regional or provincial identity over a national one. Second, Confederation left many Anglo-Canadians searching for an identity that was separate from British culture, but did not conflict with the traditions imposed by British rule. Third, though Canada finds pride in its status as an immigrant nation, a way to unite populations with deep ties to their heritage, like French Canadians, proved difficult, especially with increasingly popular Quebec separatist movements in the second half of the twentieth century. Fourth, Canada had difficulty in creating a national identity that included minorities, such as women or racial minorities like Black and Indigenous Canadians. In the decade immediately following Confederation, an answer for the question of a Canadian rallying point would be partially created in the game of hockey.

Canadian identity is frequently defined by what the nation is not, just as much as what it actually is. When Confederation took place, Canada had yet to develop a unified language, religion, ethnicity or history. There was little on which to base an identity that actually existed. Rather, Canadians would be united by a shared understanding of what they were not – and Canada was not British. The United States, born from a violent revolution, found a dramatic way to separate itself from its British origins, declaring itself independent in a statement written in blood. In contrast, Canada became a nation through a series of diplomatic meetings that declared Canada would have independent, yet commonwealth status in the British Empire. Therefore, the British heritage of Canada would not be dramatically distanced from the current state of the country. Rather, Britishness would provide a foundation for the established expression of Canadian nationalism and behaviour. British culture denoted common social cues and class structure. It was British pastimes and literature that were still popular. In order to create an identity that was unique to Canada, Canadians would need to challenge their British cultural roots by transforming them into something that suited the young nation.

The landscape of Canada also provides a cornerstone for the construction of Canadian identity. Canadians have strong emotional ties to their harsh and unforgiving climate. Canadian winters have long been held as a major component of our collective national identity. Typically, this is an innocent joke about Canadians’ tendency to live in igloos or ride polar bears to school, but the Canadian superiority associated with surviving harsh winters has extended to enjoyment of ice sports as they reflect the historical insistence that Canadians are deeply shaped by the land that surrounds and created them.

Fundamentally, hockey is the ideal sport for a mythologized Canada, and the mythologized Canadian winter frontier. It is hard-hitting and physical, demanding both skill and borderline brutality from its players. It is strategic, but also arbitrary enough that simply wanting victory and playing hard for it can lead to chance plays and game-winning goals. Hockey creates space for ‘northern’ people who are not only impervious to ice and cold, but who can also embrace it and use it to their advantage. There is not a sport that so perfectly and metaphorically encapsulates Canadian stubbornness to their environment quite like hockey. Canadians were handed thick sheets of ice, and they strapped blades to their feet, cut the ice to pieces, and called it a national pastime – how could Canadians searching for an answer for what it meant to be Canadian not fall in love with it? Hockey represented what they wanted their young nation to be: virile, tough, resistant, and passionate. As Bruce Kidd and John Macfarlane stated, “hockey is the Canadian metaphor, the rink a symbol of this country’s vast stretches of water and wilderness, its extremes of climate, the player a symbol of our struggle to civilize such a land.” Kidd and MacFarlane follow this up by quantifying that, “to speak of a national religion, of course, is to grope for a national identity”(5).

From Hockey Night in Canada, to Tim Hortons double-doubles at 6:00am practices, our national stereotypes have come to fall into three distinct categories: maple syrup, politeness, and hockey. As hockey and Canadian identity were both constructed simultaneously, it follows that hockey would become a cornerstone of what Canada believed itself to be. Canadian identity is undoubtedly constructed. It has been purposely built for a nation of immigrants, with differing races, genders, languages, and beliefs, in which hockey is common ground. Though there are important shortcomings in the sport to recognize, including its intensely limited demographic of professional players (namely often white, heterosexual men from middle to upper-middle class backgrounds), those who participate in the amateur leagues and the fandom of hockey come from all walks of life. There is no requirement to participate in hockey but the love of the game, something that has been endorsed by campaigns like You Can Play, Black Girl Hockey Club, and the Hockey Diversity Alliance. Hockey has a ways to go in terms of achieving true equality in the sport, but steps are being made to create a more welcoming and inclusive environment that truly reflects Canada’s commitment to diversity.

Road hockey, as pictured above, is a popular community pastime for children outside of the rink. Unlike the expense of playing organized hockey, road hockey simply requires sticks, a tennis ball, and a group of willing players. Road hockey is inclusive, fun, and quintessentially Canadian.

Niagara and Hockey

Niagara is a place rich in hockey history. From our OHL’s Niagara IceDogs, to beer leagues, to the Brock Badgers, there is always plenty of hockey to watch in this area. Stan Mikita, who would represent Canada in the 1972 Summit Series was raised in St. Catharines, as were other major hockey figures like Alan Eagleson, Gerry Cheevers, Brian Bellows, Sarah Bauer, and Riley Sheahan. Niagara is even home to players after retirement, including Hall of Famer, Marcel Dionne, who currently lives in Niagara Falls. In the 1960’s and early 1970’s, the Boston Bruins farm team, the Flyers, were even located in Niagara Falls.

The Toronto Maple Leafs’ last Stanley Cup win in 1967

Despite Niagara’s connection to the Bruins, at The Brown Homestead, we proudly possess a strong relation to the Toronto Maple Leafs … outside of Kaitlyn being a huge fan (6). Recently, a descendant of the Powers family named Don Jessome fondly recounted to us the story of watching hockey in the John Brown House, including in 1967, when Don and his grandfather Charlie Powers, were able to see the Leafs last hoist the cup from the comfort of what is now the home’s dining room. While we were not lucky enough to see the Leafs break the longest Cup drought in the league (or break their round one curse) this year, it’s not hard to see how Leafs fans saying “next year… next year’s our year” is getting less and less unrealistic. There’s still a lot of hockey left to play in the 2022 NHL Playoffs, and much of the outcome is up to chance, passion, and determination. Above all, it’s up to the players, eager to hoist a Cup not only representing the long history of the sport, but also reflecting an icon of Canadian identity. And after two years of empty seats, fans are back in the arenas, participating in a major element of our culture: the euphoria of the good ol’ hockey game.

It was Harry Sinden, Team Canada’s coach in 1972, who noted that “Hockey never leaves the blood of a Canadian”(7). In many ways he is correct. This country’s heart beats for a sport that embraces many elements of our cultural myth. If hockey is inherently running in the bloodstream of this nation, then it is us who put it there. Hockey is Canadian, insomuch as Canadians have decided to make it so. There is power to an identity that is chosen, rather than assigned, and if the Stanley Cup Playoffs prove anything, it is that no matter what, Canadians undoubtedly choose hockey every year.

(1) The origins of hockey are hotly debated, with each Canadian province making a claim to being hockey’s birthplace. The reality is that hockey developed from a number of sports and sporting traditions. Carl Gidén, Patrick Houda, and Jean-Patrice Martel have published a detailed account of the various claims to the invention of hockey and their legitimacy in 2014 with the Hockey Origins Research Group (HORG). They reached the conclusion of a sport of European origin that was altered by Canadian settlers, which ignores the Indigenous elements of the sport such as the speed of play, the use of physicality, and the play taking place on ice. The actual origin of hockey is less important in the context of this research than how hockey developed alongside Canadian nationalism. For more information on the origin of hockey see: Gidén, Houda, and Martel, On the Origin of Hockey (Stockholm: Hockey Origin Publishing, 2014). The claim in this paper is based on “Victoria Rink,” The Montreal Gazette, 3 March 1875, 3, which chronicles the first known instance of an organized game of indoor hockey.

(2) “Victoria Rink,” The Montreal Gazette, 3 March 1875, 3.

(3) Michael A. Robidoux, “Imagining a Canadian Identity: A Historical Interpretation of Hockey and Lacrosse,” Journal of American Folklore 115, no. 456 (2002), 2014.

(4) Quoted in Tyler Shipley, “Hockey Invented Canada: Questioning the Myth of Manufactured Nationalism,” In The Spaces and Places of Canadian Popular Culture, Victoria Kannen and Neil Shyminsky, eds. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 2019), 342.

(5) Bruce Kidd and John MacFarlane, The Death of Hockey (Toronto: New Press, 1972), 4.

(6) Kaitlyn was born into a Leafs home. She did not choose this.

(7) Harry Sinden, Showdown: The Canada-Russia Hockey Series (Toronto: Doubleday Canada Ltd., 1972), 38.

Author Bio

Kaitlyn Carter [M.A. History, Western University] is the Fundraising Coordinator at The Brown Homestead. Kaitlyn has specialized in the modern period in Britain and Canada since 2018. Her M.A. thesis (2021) focused on the gendered nationalism exhibited by military and sporting Canadians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and she has published multiple papers on the unique national identity associated with hockey in Canada. In September, Kaitlyn will be departing The Brown Homestead to pursue a PhD in History at the University of Roehampton London as a member of the Techne Doctoral Training Program funded by the AHRC. She is openly a Toronto Maple Leafs fan, and as such will accept your condolences at your earliest convenience.